Music Sync

How a chart’s patterns fit a song’s rhythms and intensity.

Pattern creation is fundamental to the gameplay of XDRV charts. Obviously, players need to be given something to do for the duration of a song. Less obvious is that a chart’s quality is often grounded in the ideas behind its patterns. Experienced XDRV charters use knowledge of the game’s mechanics, common patterns, and per-chart goals when patterning for a certain song.

In next to all rhythm games, the fundamentals of a “good” chart can be broken down into 3 maxims:

Music Sync

How a chart’s patterns fit a song’s rhythms and intensity.

Visual Appeal

How a chart’s patterns look, including clarity and balance.

Fun

How a chart plays on all intended playstyles.

For most cases of charting, all three of these factors contribute to the player’s experience with a chart and a chart’s perceived quality. Music sync, visual appeal, and fun can all be achieved through various means.

When charting, there are several basic ways that patterns can be made. These ways can be grouped into different styles of charting. Effective charters can use a combination of these styles to get the best results.

Pitch charting is a style of charting in which notes are placed relative to each other in terms of their pitch. If a proceeding note has a higher pitch, it may be placed in a lane to the right. If a proceeding note has a lower pitch, it may be placed in a lane to the left. If a proceeding note has the same pitch, it may be kept in the same lane. This relationship can be reversed so that higher pitches are to the left and lower pitches are to the right.

Pitch charting not only follows music sync, but is also one of the most music-accurate ways of charting. As it replicates movement across an instrument, it is often naturally fun to play. However, some melodies may chart to patterns that are unreasonably difficult, static, or messy. The best way to tackle this issue is to avoid rigidity. Different relationships can be used for similar changes in pitch, and the relationship of lane to pitch can be reversed whenever the charter sees fit.

Sample charting is a style of charting in which different note types correspond to specific sounds. If you have a bass-kick pattern, for instance, tap notes may be charted to the kicks and hold notes may be charted to the bass. You may also give these note types specific lanes. Kicks may stay to lanes 1-3, while bass stays to lanes 4-6.

Sample charting can use different quantities of notes to emphasize different sounds. For instance, if a kick-snare pattern is present, many charters will make the kicks single notes and the snares double notes (also called a chord).

Sample charting is, again, great for music sync, as these separations, when done well, are easily absorbed by players. Like pitch charting, however, some unbalanced or boring patterns can result. Again, avoiding rigidity is an easy fix to these issues. This may mean redefining the constraints that you have on the patterning. Maybe you need to add a few more lanes or swap input mappings halfway through.

Essential charting is the method of reducing complicated rhythms to simple, essential patterns. This typically does not mean simplifying the rhythms used. Rather, placement of notes are simplified to patterns that are common across other vertical-scrolling rhythm games. Essential charting is a useful tool for converting unwieldly sections of a song to enjoyable, yet representative patterns.

These three styles, in isolation, can get you a good bit of the way in terms of charting for XDRV. With that said, charting is as much a mechanical process as it is artistic. Throughout your creation of patterns, you can make decisions that deviate from the above methods yet improve your chart’s quality. Below are some of these considerations.

For new charters that see the playfield is divided into two halves (three lanes for the left half, and three lanes for the right half), it may feel intuitive to have long stretches of patterning be on one half. Unfortunately, doing this can result in patterns that feel excessively technical. It can also make sections of a chart look empty or unbalanced. When charting, players should primarily consider the 6 lanes as a continuous space rather than two separate spaces. This means that a single instrument could be charted in all 6 lanes (potentially 8 lanes if gears are used as well). With that said, limiting a section to one hand’s inputs can be fun and purposeful, especially for more technical charts.

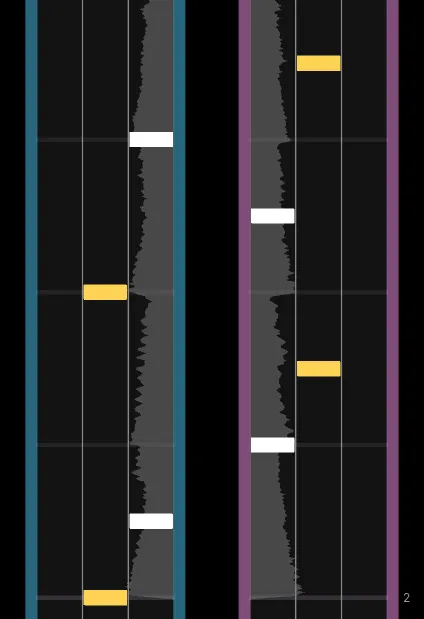

|  |

|---|---|

| Separate | Continuous |

In many songs, a specific melody or rhythm, best represented by a pattern of your choice, may repeat a few times. To avoid this pattern becoming repetitive, it can be mirrored where it recurs. This makes the pattern feel fresh while maintaining the relationships between notes.

|  |

|---|---|

| Unbalanced | Balanced |

Mirroring can also help considerably with hand balance. When charting, it is a good idea to make sure that note placements are not too concentrated on one hand. Mirroring sections can make a chart more fair for players of different hand dominances (whether they be left-handed, right-handed, or ambidextrous).

In many base game charts, charters exclude certain lanes when patterning specific sections. Limiting lanes can be good for controlling difficulty on dense sections, making the player responsible for less distinct inputs. The strategy can also be useful for creating unique patterns that better represent the sound of a section. When omitting lanes, charters will typically omit lanes symmetrically; either the two outer lanes, two inner lanes, or two middle lanes. Occasionally, especially on easier difficulties when a drift is used, the lane furthest from the drift direction is omitted. (Left drift omits lane 6, right drift omits lane one.) Charters can get very creative, though part of the appeal is in contrast, so don’t overuse it!

When charting, charters should consider how the difficulty of the chart changes with the song. Typically, more intense parts of songs such as drops, build-ups, and speed-ups deserve more difficult or more technical patterns. Conversely, calm parts of a song should receive easier, less busy patterns.

Common practice in many .xdrv charts is to simplify complicated or dense rhythms to simple patterns, where sounds of less emphasis are purposefully not recognized with a note. This process is known as syncopating. Syncopating is great for limiting difficulty in easier charts, but it is also great for maintaining proper difficulty progression in harder charts, especially in slower sections.

Although it may be tempting to represent multiple elements of a complex composition with different notes and patterns for each element, it can quickly become messy. It is typically better to omit some elements to represent one or two key elements of a composition than try to represent multiple elements poorly.

Charting to difficulty is the process in which a charter creates patterns with a specific difficulty rating in mind. Charting to difficulty can be good in stabilizing the difficulty progression of a chart, but striving for the wrong difficulty can result in undercharting (where the song’s intensity exceeds the chart) or overcharting (where the chart’s intensity exceeds the song). Newer charters should not chart to difficulty too strongly until they have a good understanding of EX-XDRiVER’s difficulty scale, which can only come with time and purposeful observation.

If you are familiar with the step-based rhythm game scene, then you are probably also familiar with stamina and tech charts. Stamina charts are charts where lengthy streams of notes are used, which require a lot of stamina to hit completely. Tech charts, on the other hand, are charts that focus more on tricky rhythms and combinations of simultaneous notes, known as chords.

The basic concepts of “stamina” and “tech” charting can be applied to XDRV charts as well, despite the game not being step-focused. In fact, you can find many of these tendencies in base-game XDRV charts. Charts like CANDYLAND and LUMINOUS RACE are more akin to stamina charts, while charts like And So You Felt or City in the Clouds are more tech-adjacent. You don’t have to commit every chart to one of these styles, but when warranted, it can give your chart some flavor.

As demonstrated by this article, there is a lot of nuance as to how XDRV charts can be patterned. Don’t be too worried about adhering to these principles. Rather, you should allow these principles to guide you through difficult charting decisions. The next section will go over common note and hold patterns that you can use in charts.